This might be the first time I really wished I track where I find the books that end up on my to-read list, because this one was a direct reference from somewhere--another book, a blog post--and I found reading it to be SO interesting that I wish I could go back and retrace my steps. The book Back from the Land: How Young Americans Went to Nature in the 1970s and How They Came Back, by Eleanor Agnew, started out by scratching a very particular itch that I have and ended up leaving me feeling like I had some insights into the author's personal defense mechanisms and personal narratives.

The itch--the reason I picked up the book--is because I love "huh, farm life maybe isn't so idyllic after all" stories. City folk moving to the country and trying to chop enough wood to get through the winter amuses me. City folks being shocked at how heavy buckets of water are makes me feel--here, I'm admitting it--superior.

The itch--the reason I picked up the book--is because I love "huh, farm life maybe isn't so idyllic after all" stories. City folk moving to the country and trying to chop enough wood to get through the winter amuses me. City folks being shocked at how heavy buckets of water are makes me feel--here, I'm admitting it--superior.I'm not proud of it. Honestly, I don't deserve the superiority; I'm not the one who woke up twice a night to feed the wood stoves when I was a kid. But my parents did, every night. My father had to tromp 100 yards through the snow to feed the greenhouse fires, too, every night of February and March and most of April, for years. I just had to fill the wood box in the entryway from the shed in the barn, and even then, not often. I was spoiled.

But I know how hard all this stuff is, which is why I get satisfaction watching noobs learn things that my mom is an expert on (cooking on a wood stove is hard!). It's similar to what I enjoyed about Kristin Kimball's The Dirty Life: A Memoir of Farming, Food, and Love. Kimball brought a wry self-deprecation to her recollections of starting this out. Or what I liked about the This American Life segment called "Farm Eye for a Farm Guy." Listen to it--it's only 20 minutes long and it's super great.

This is what drew me to the book, and the reason why, as I read the first chapter or two, I kept reading passages out loud to my family and chuckling. These folks are so naive!

What kept me reading, I think, was the insights into the author. Eleanor Agnew moved from, I believe, Pennsylvania with her husband and two young sons to live on a homestead in Maine. (If you are going to live off the land, why would you pick a state in which winter lasts 8 long months? Did you even think about this?)

The book contains her own reminiscences and those of many other friends and acquaintances, back-to-the-landers from all over the country who lived everywhere from communes to wilderness to small farm towns. She seeks out the threads of commonality to their experiences--including how they end--and that's interesting and worthwhile. But in the end, it is also very anecdotal, and the citations and statistics drawn from sociology and economics don't add any rigor to what is essentially a group memoir. As a memoir, it works somewhat, even with so many voices and experiences represented. As a study, even a pop-social science study, it doesn't stand up to any scrutiny.

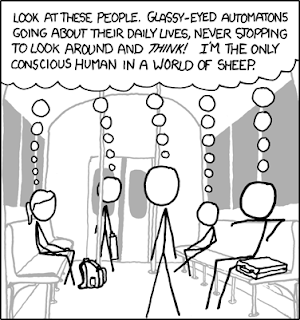

The author has an agenda: she knows that their philosophies were sound, even if they weren't strong enough to live them out. She believes that "mainstream society" is full of materialistic sheeple, but back-to-the-landers--even those who have rejoined the mainstream and are now architects and college professors--are still pure of heart. She describes how much she values nature, and how she gets such bliss observing the koi pond in her backyard in the subdivision she lives in. See, she values nature in ways that other suburbanites do not.

This sense that the internal lives of the people who share her beliefs are virtuous and consistent and justify whatever outward choices they're making, while the internal lives of others who make the same outward choices are suspect, is pervasive in the book. She talks about how hippies didn't need fancy new cars, and then she discovers that wow, an old car in a Maine winter takes a lot of upkeep and often means getting trapped in your backwoods home. She even says explicitly that she would not mind at all having a new car, because it would be a safe and reliable connection to the outside world, but doesn't follow that line of thought through to the notion that maybe other people who get new cars have useful reasons, whether practical or psychological.

| |

| xkcd.com |

Also, darn it, she misused words and ideas in a few places. I don't want to be pedantic, but "I was donned in my uniform" is not how you use that verb; the fact that the average life expectancy was 18 years does not mean that no one lived to grow old; the goal of the pioneers was not to live in harmony with the land, but to gain economic security and prosperity so they could improve their lifestyles. They lived in dugout houses so they could later afford nicer ones, not because they wanted to live in dugouts. They would not have said no to running water.

So in the end, my satisfied schadenfreude about the naive kids getting in touch with mother earth was replaced by a kind of sad schadenfreude about baby boomers who still think that they have it all figured out. I'm reminded of my father's old saying: "My opinions may change, but not the fact that I'm right." Agnew has readjusted her view of the world so that no matter what they do, she and her friends have cornered the market on virtue.

2 comments:

"Agnew has readjusted her view of the world so that no matter what they do, she and her friends have cornered the market on virtue."

TRUTH.

I love it. This makes me think of No Impact Man.

Post a Comment